On career changers in education

Mid-career professionals could be the solution to the teacher shortage

The recent DESE review into Initial Teacher Education is a whopper and most of it says a lot of the things we have long known about ITE, but have been waiting to officially hear. There is about a year’s worth of newsletter posts within its pages but I want to focus now on something that’s deeply personal to me: the challenges of changing careers.

I worked in fashion and advertising for many years. It was a very ‘cool’ career and it took me all over the world. Over time, I began to feel very disconnected from my work. I was an agent for photographers and illustrators, and so there were several layers of authentic, creative work between me and the end product. I was just the catalyst. One day in about 2010, I was asked to travel to Mexico and sit on a beach while one of my photographers shot a Corona beer campaign. I sent my producer instead and thought, it’s time to get out. The problem was, I wasn’t saving any lives. The ‘industry’ didn’t mean anything to me any more.

Unfortunately, I had never finished a university degree, despite starting several. My completed subjects were more than 10 years old, so I had to start again. I took work as a teacher’s aide and in disability support, and plodded through four years of study. Mine was the last 12 month course in 2014, as far as I know.

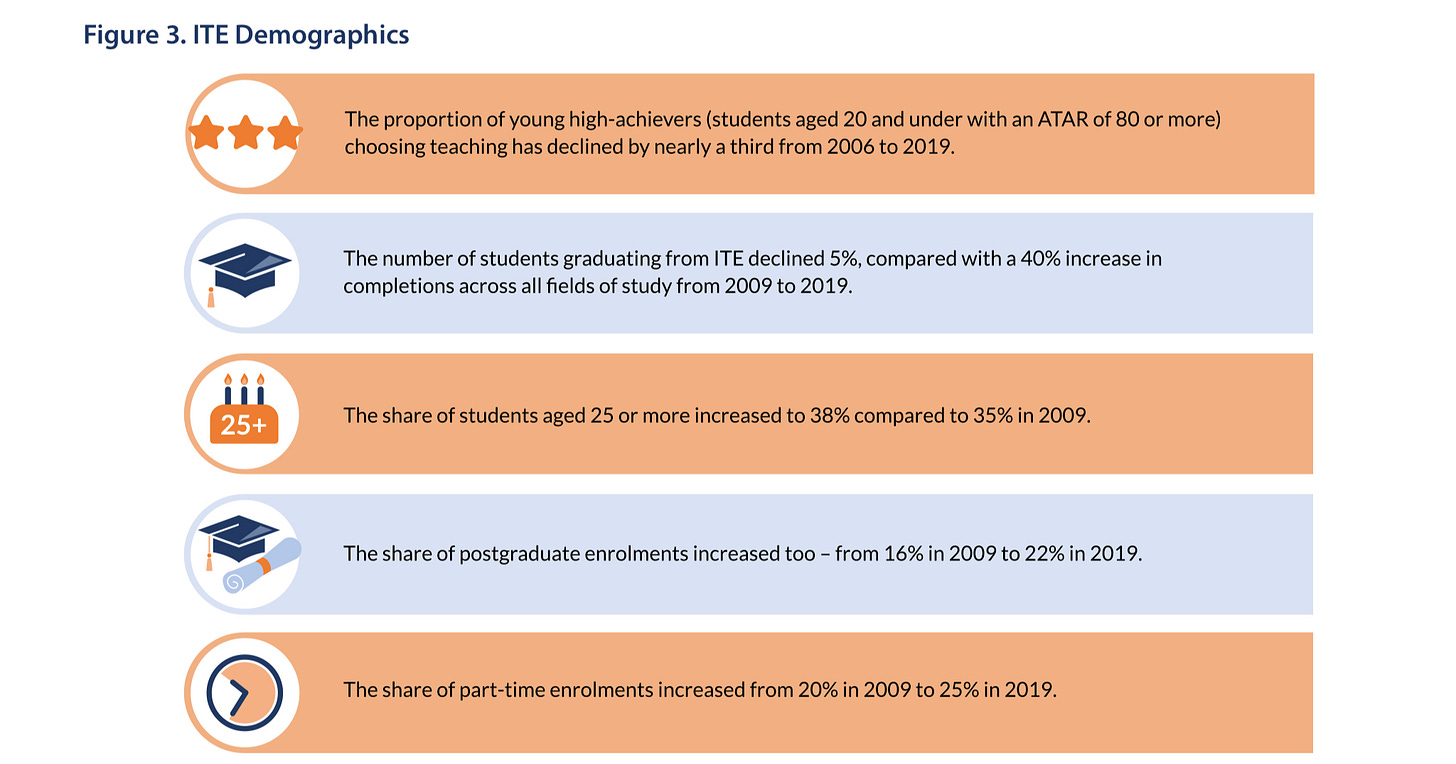

The report lays out difficulties in getting people to enter teaching. As Jenny Gore rightly says, there’s often a focus on high achievers, which in itself can be damaging to the self-concept of existing teachers, who seem to be pitted against this cache of unrealised and superior potential. Mind you, an ATAR of 80 hardly places these students at the height of the intelligentsia. The subsequent four facts below seem to suggest that some of our biggest and most valuable workforce gains are to be made in attracting partially qualified people who have made a conscious decision to teach and have the maturity to make decisions that stick.

Obviously my experience means that I’m going to wholeheartedly support moves to reduce the training requirement to change careers. It’s difficult to argue that two years of poor training (as exposed by this report) is better than one. Teachers were once trained at the equivalent of the TAFE level and we are sadly losing a lot of those long-time outstanding practitioners now as they retire. I could be wrong, but I haven’t seen a correlation between longer ITE and retention or even teacher quality - whatever that is.

Jenny Gore argues that shorter courses erode the perceived professionalism of teaching, but I challenge you to find a person in the community who connects shorter courses with a lack of rigour in teaching. At the same time as this, the DESE reports that most people think teaching is a one year or less course anyway!

Criticisms are often levelled at programs like Teach for Australia, where candidates enter the classroom after a very short time and are essentially paid while they study. The data presented on this is (deliberately?) tricky. It seems that the program is a good source of new STEM teachers coming from industry, showing overall “high retention rates, with 88 per cent of teachers remaining in the classroom for more than two years, and 72 per cent of all TFA alumni still teaching in schools.” To me, this doesn’t seem particularly high. We want teachers in the classroom for far longer than two years, and the program is losing about 30% of its candidature overall, a rate of loss that is marginally better than the oft-quoted statistic of a 1 in 3 attrition rate after five years. But I will say that while working and studying have their challenges, this program removes a huge barrier to career changing.

Gore also argues that the complexity of teaching necessitates a long course. I’ve written about the criminal amount of time wasted in my ITE here and hopefully this will change as a result of this review. But despite the complexity of teaching, and despite deficiencies in ITE and the ostensibly inferior one year course, after seven years my career changing colleagues and I are thriving in teaching. Two were targeted grads, both by selective schools. One is now Head of Department at a top 10 school, one works for the Department. Another is Assistant HOD at a high performing boys school, another STEM teacher is HOD after a career in engineering. Most came from media, like me. Another had a doctorate in an unrelated field. It is interesting to see that most of us now spend less time in the classroom and the report does address this. A newsletter for another day.

One of the things we all still have in common is the continued surprise about how much harder teaching is than our previous roles. I do think, like Rebecca says below, we need to address preparedness for the classroom and seriously rationalise and rethink the workload of teachers. These moves, as much as anything, will help retention rates.

It’s yet to be seen how much of this report will be implemented. With a potential change of government, who knows where the focus will lie. I’m glad to see moves that will potentially make it easier for people like me to enter teaching.

We older people sometimes feel like our brains are slowing down. But this actually works in our favour. What we lose in fluid intelligence and processing speed, we gain in crystallised intelligence, where our decisions are based on knowledge and experience. We need more teachers who have made a conscious and considered decision to ‘save lives’ and we need to set up systems to get out of their way.

https://robertbuntine.substack.com/p/a-recipe-for-good-teacher-training?utm_source=twitter

Rebecca B. Thank you for the interesting and courageous article. When I taught it was not possible to tell the post war 6 mth teacher trained from those who had spent several years at university. Like acting.. some could do it and others couldn't.