I think one of the great things that postmodernism and critical theory have done is to bring intro question the value and diversity of the canon. Theory, done well, plays with ideas about authority, accessibility and the identities and values that are represented and reinforced in literature. I think the key element here, and one that is often de-emphasised, is the critical.

To democratise the canon, the canon needs to exist. Those who want it gone lose the opportunity to investigate values and text structures over time, and the chance to examine what it is about these works that compels the greater Western world, even after hundreds of years. Arguments against its existence reflect - in my view - a lack of understanding about the rich opportunities for critical thinking that arise from deconstruction. I would hate to think of Bronte being cancelled because of colonialist representations. Jean Rhys’s apparently felt this way too, and her response in Wide Sargasso Sea is a rich exploration of Bertha’s story and treatment.

I often hear English teachers say, “Well, you never know what will be in tomorrow’s canon,” and suggesting that the pop culture of today will be the high art of tomorrow. But again, this is a misreading of postmodernism. Art that plays with popular culture is rich with irony, craft and meaning, frequently drawing on features and ideas in canonical works. And really, we kind of do know what will become the canon of tomorrow. And it’s probably not something that was of-the-moment just yesterday. I have written about Nassim Taleb’s thoughts on this here. Quality and universal ideas endure but both are under threat from the pervasive relativism of cultural and identity politics that is slowly spreading through education.

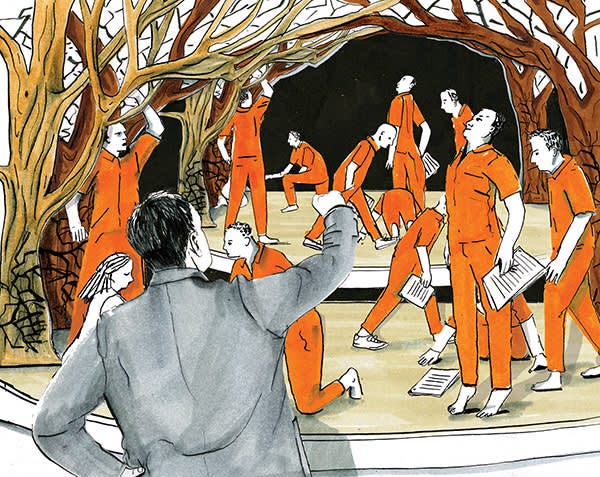

I’m teaching Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed again this year. It democratises the canon in a kind of meta way, the way we know and love about Atwood. The novel is a playful take on The Tempest, exploring the personal journey of a flawed and selfish leader (Prospero as Felix), who discovers the healing power of art by democratising the canon for a group of low-security prisoners. Atwood is an advocate for education as a key tool in the prison reform box. The main character Felix doesn’t engage the prisoners by showing them the Helen Mirren film version! He opens up the play for participation and reinvention, enabling the prisoners to see themselves in the characters and rewrite their fates. In this way, the prisoners experience the power of a classic play and answer back to stereotypes and injustices of Shakespeare’s time and their own past.

To me, democratising doesn’t mean a watering down, an inclusion of pop culture or a popular vote. It means engaging in dialogue with a living, breathing, soft-edged but strong-centred body of work that was written to challenge, and remains challenging and contested. And where individuals struggle to access this body of work, education and play come together. Democracy means participation.

Interesting perspective. I think many academics as well as secondary school teachers would like, indeed, to abolish the canon rather than democratize it. I have heard, from my perch in North America, far more calls for abolition than for democratization. As for Atwood, I think that her work, especially The Handmaid's Tale, is well on its way to becoming canonical itself. (At least I hope so.)