On how to develop independent learners

A new lens on self-determination theory

Regardless of our beliefs about pedagogy, there is one thing that unites teachers: we all want our students to achieve independence. If I had to generalise, I might suggest that progressive pedagogies aim to see this fairly quickly and perhaps more spontaneously than with more explicit approaches. Think of Rousseau’s Emile who learns naturally through experience rather than any kind of didactic instruction. Independence here is not just a goal of education but integral to the child’s development.

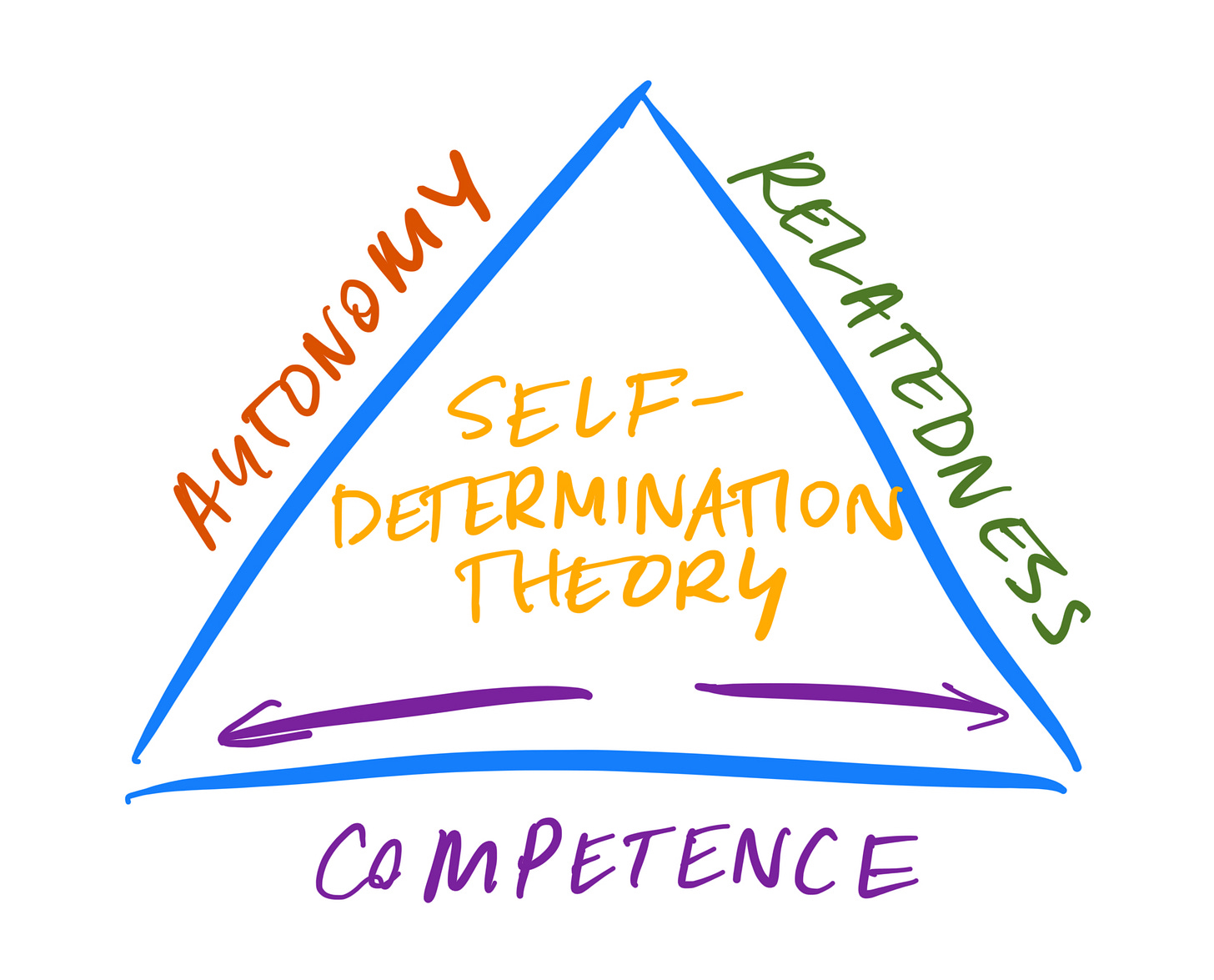

Before I started my research, I believed autonomy was purely about student choice. The need for autonomy springs from Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory, with the other basic psychological needs being relatedness and competence. In education, these are usually framed as autonomy support, involvement and structure. The literature about autonomy, especially when it comes to self-regulated learning, does indeed point to freedom of choice and student-directed approaches, especially in relation to self-directed learning.

I don’t often talk about my own research because I am deep in novice-land. My research involves reliance on two giant textbooks, a lot of ChatGPT, a fair bit of pain with watching YouTube software tutorials, and pestering my supervisor – and anyone else who will listen. It’s hard work. Like all this nitty gritty, the concept of autonomy support as a construct was brand new to me. The first time my reality was confronted was when I discovered that there’s an under-exposed but consistently demonstrated connection between autonomy support and teacher-provided structure.

I had assumed that autonomy support belonged to a certain group of pedagogies – in practice and in the literature, it is a neater ideological fit with student-centred approaches. But here’s the paradox: if students are competent in very few ways, then they have very few choices available to them. Autonomy and structure are often presented as dichotomous, and competence is sometimes seen as something of a poor cousin to the warmer and fuzzier feelings of belonging and autonomy. But if I had to draw SDT as a diagram, I would place competence at the bottom of the triad, supporting all the other needs that schools meet.

The relationship between autonomy support and structure is well-known to SDT researchers, but I think it deserves more play. The key is knowing when competence (think of it as mastery) is achieved. A sprinkle of ‘just in time’ explicit teaching in a project-based setting may contribute to regular bouts of cognitive overload, rather than a well-planned and chunked sequence that develops mastery and transfer over a longer cycle. It turns out that explicit teaching (structure, indicated by scales like load reduction instruction), is needs-supportive. ‘Need frustration’ arises when teachers withhold knowledge from students or expect independence too soon.

Regardless of tribe, teachers want the same thing. We can take shortcuts to achieve the illusion of independence – students doing their own thing, some of them probably having fun while they’re learning, many not mastering much at all – or we can take the seemingly more difficult path to long-term learning. As Zimmerman said, the way to become an independent learner is not by practising being an independent learner.

The lens you offer makes so much sense from the benefit of teacher experience. Goes against everything we assume about learning and were taught. The word 'competence' never rated a (meaningful) mention in ITE but 'independent learning' often did.

Children feeling competent is the foundation for learning. Your image of the child as competent is very important. It sends a message that you view all children as competent, which is critical for children's learning and development. This helps children work to master what is being taught.

Autonomy and structure are both important. Teachers structure the environment in which a child is taught. If you know what the child is currently capable of mastering - the knowledge and skills they already have- you can structure choices for them that will provide the development of autonomy, and if you are aware of each students' needs, the teacher can also structure the kind of support that child needs that will lead to mastery of content.

A big question to contemplate is how do you know whether the child actually understood what they wee supposed to learn. What are you using to determine this?