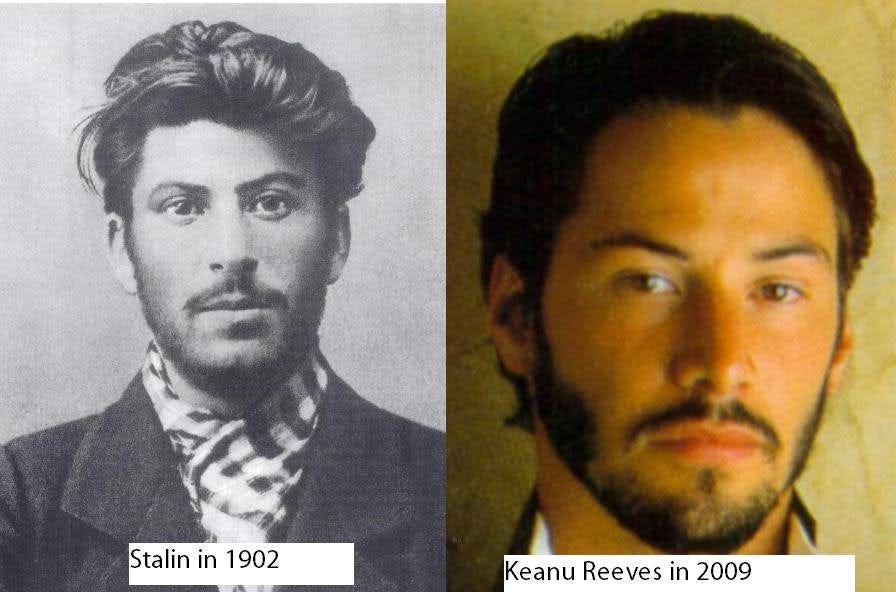

Most models of leadership are noble in their aims. What could possibly be the problem with leadership that centres on learning, shared power distribution, leadership that shows vision and the promise of transforming schools? Well, it’s interesting to note that leadership is still largely a theoretical construct. And we all know what happened when Karl Marx forgot to leave a roadmap for his vision. We don’t just study Stalin for his good looks.

In true Birch style, I’m being facetious, but the more I investigate leadership, the more I’m convinced that successful models rely on selecting for buy-in from staff, rather than simply creating cultures of buy-in. For example, Vivian Robinson’s effect sizes for influential leadership practices show strategic resourcing (code for staffing) as a powerful tool, but a lot of the other practices potentially tie in to this. If we hire for practitioners who welcome goals and expectations, engage in professional learning willingly, and respond well to a focus on quality teaching, then it’s difficult to extrapolate which is chicken, which is egg. Is it the culture or the quality of staff that makes the impact? Often when a new leader takes over and lays out her vision, a natural attrition occurs. Staff who don’t share the new vision tend to desert, leaving a greater proportion of teachers and middle leaders who are prepared to work towards the new leader’s stated goals.

When we look at barriers to different models of leadership, one theme comes through strongly: each relies on a strong team, and conversely each model can struggle under the inertia of legacy staff. While Dylan Wiliam promotes the idea of developing the staff one has, I tend towards the idea that selecting for teacher qualities has a similar effect on a school’s results to selecting for student intelligence and parent buy-in.

This combination of creating the conditions for attrition of non-conforming staff - namely goal setting for teachers and leaders, higher standards and accountability - can be seen in transformational leadership, where the main criticism of the model is the tendency toward top-down vision, rather than the development of a shared purpose. It’s easy to see how attrition would prompt ‘transformational staffing’ where non-compliant role applicants might be filtered out.

Likewise successful instructional and distributed leadership models require highly skilled teacher-leaders. One of the biggest barriers to true instructional models is time for professional development, observation and reflection. I have seen aspects of this model adopted but often teachers don’t have time (read: money) invested into their work to the extent that they would see a marked improvement in their practice. While developing a school culture with student learning at its centre is of course desirable, it’s far easier to hire for the qualities that make this model work.

And so we are left with models of ‘what works’ but the combinations of strategies, the true root causes of success and the resources needed to implement them are left unsatisfyingly undefined. I suppose one way to look at leadership and vision is to imagine the counterfactual: what happens when we have at least some superstar staff, engaged students and parents, a general feeling of goodwill and a vague but positive shared purpose? But then take this scenario and imagine what happens when a lack of shared vision, coherent leadership and support structures allow those same precious human resources to atrophy?

We’re left with the moral imperative to lead that we started with. And possibly that’s enough.